I posted this a few years ago, but as it’s the centenary of the Battle of the Somme, I thought it could be the right time to give it another airing.

I never knew my grandfather. He died a fair few years before I was born, and when I was growing up it was a rare occasion when he was mentioned in conversation by my father. Most of the tales were as dark and murky as the post-WW2 Manchester in which they were set.

There was only one picture of him in our family’s possession; a small, grainy black and white shot of a serious man with an uncanny resemblance to Peter Cushing. The only link to a man who, in my mind at least, hadn’t really been the ideal bloke and who I was a little pleased never to have met.

Then my dad rediscovered another memento his dad, carefully stored in the bottom of some box or other safely stowed in a forgotten corner of the attic.

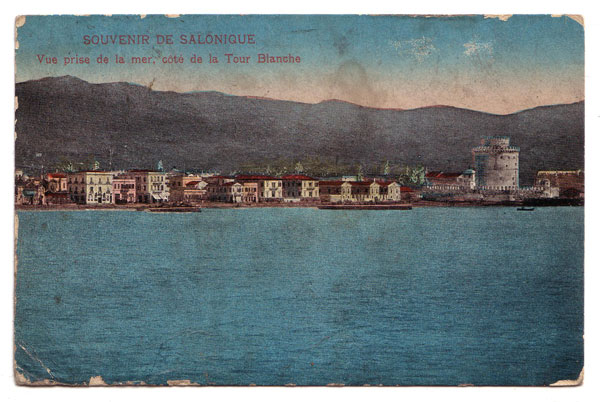

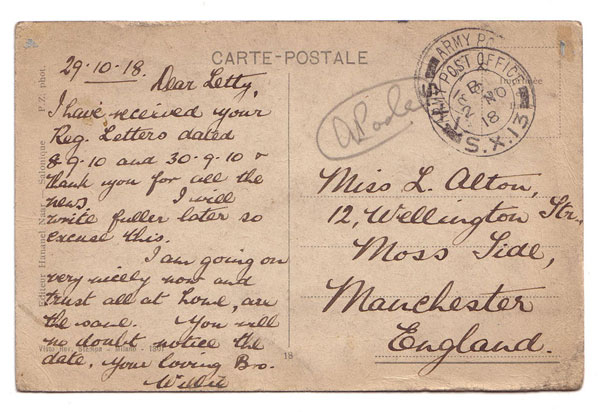

It was a postcard from one of the forgotten fronts of WW1, sent by the young William Alton to his sister back at the then family home in Moss Side, Manchester.

Not knowing anything about the reason he was there, or about the man who bequeathed me a middle name, I decided to do a bit of research.

Not many people (war historians excepted) are even aware that the British sent soldiers to Salonika in Greece. But that’s what they did, setting up the Macedonian front to help Serbia against a combined attack by Germany, Austria-Hungary and Bulgaria. Initially derided as “the Gardeners of Salonika” due to the cushy and stable nature of their posting in comparison to the boys in the trenches of Belgium and France. This force was soon bloodied by a relentless pattern of attack followed by counter-attack in vain attempts to break the stalemate – and the equally lethal offensive waged by the legions of mosquitoes that made life a misery and rendered more men incapable of fighting than the enemy managed to.

At some point, William, who had signed up at the age of 16 like many young men at the time who were eager for a bit of adventure and the chance to have a bash at ‘Johnny Hun’, ended up right in the thick of it.

This description of one particular forgotten engagement on the dusty, sun-baked hillsides says it all. It’s an excerpt from a piece written by ‘An Unprofessional Soldier’ on the Staff of 28th Division. He entitled his paper: “I saw the Futile Massacre at Doiran”:

Our attack on ‘ Pip Ridge’ was led by 12th Cheshires. The battle opened with a crash of machine-gun fire, and a cloud of dusty smoke began to blur the outline of the hills, Almost immediately the advancing battalion was overwhelmed in a deadly steam of bullets which came whipping and whistling down the open slopes. Those who survived were followed by a battalion of Lancashire men, and a remnant of this undaunted infantry fought its way over the first and second lines of trenches – if indeed the term ” line ” can be applied to a highly complicated and irregular system of defence, taking full advantage of every fold or contortion of the ground. In its turn, a Shropshire battalion ascended the fatal ridge. By this time the battle of the ” Pips” was a mere confusion of massacre, noise and futile bravery. Nearly all the men of the first two battalions were lying dead or wounded on the hillside. Colonel Clegg and Colonel Bishop were killed; the few surviving troops were toiling and fighting in what appeared to be inevitable and immediate death. The attack was ending in a bloody disaster. No orders could reach the isolated cluster of men who were still trying to advance on the ridge. Contact aeroplanes came roaring down through the yellow haze of dust and smoke, hardly able to see what was going on, and even flying below the levels of the Ridge and Grand Couronne. There was only one possible ending to the assault. Our troops in the military phrase of their commander, “fell back to their original positions” Of this falling back I will say nothing. There are times when even desperate heroism has to acknowledge defeat.

You can read the full article here if interested: http://www.1914-1918.net/salonika.htm

William appears to have dodged the bullets, bayonets and shrapnel but not been so lucky with the aforementioned mozzies, being laid low by malaria along with many of his comrades. It was this that took him away from the action and to hospital in Salonika, from where he sent this beautifully penned postcard to his sister back home as he was recovering. Maybe his mind still needed a little more recuperation as I can’t understand why his sister would have sent registered letters to Salonika in 1910, but the message is touching and the handwriting absolutely stunning. If he was from a more contemporary Moss Side he’d most definitely be king of the taggers.

When his health was judged good enough for him to be returned to active duty, he was then sent to Constantinople (not Istanbul) and then on to Dublin where the British Army decided to keep the fighting going even thought the Great War was now over.

He managed to avoid a visit from Michael Collins and the boys, then returned to Britain; along with a whole army of other young men, a shadow of his former self whose life would be forever overshadowed by events that had happened during WW1.

Leave A Comment